Inclusion

An Interview with Shelley Moore

Reprinted from 3.21: Canada’s Down Syndrome Magazine (Issue #4: The Back to School Issue). Click here to download the full magazine.

3.21 Magazine had the opportunity this summer to sit down with inclusive education advocate Shelley Moore to get her thoughts on what real inclusion looks like, why it matters, and where we’re at with inclusion in Canada.

3.21 Magazine: Tell us about Shelley Moore.

Shelley Moore: Hi everyone! I’m Shelly Moore. I am a PhD candidate at the University of British Columbia. My research is in inclusive education. I’m specifically looking at secondary schools, because that’s often where inclusion needs more support. More precisely, my research is looking at the question: How do we include students with intellectual disabilities in secondary school academic classrooms? The inclusion movement is near and dear to my heart because I struggled in school growing up. I am a researcher, but also a teacher, consultant, speaker and advocate – my role changes every day.

3.21: When did the importance of true inclusion first strike you, and why does it matter?

SM: My perspective and my understanding of inclusion has shifted so much over my career. I remember when I went to school, I really struggled. I only felt successful in one year: eighth grade. Ironically, that year, I went to an alternate school. Because of that experience, when I first started my career, I didn’t believe in inclusion. I thought, “My needs didn’t get met in my neighbourhood school; my needs were met when I was in a school that was specific for my needs.”

For my first job, I worked in a grade four or five classroom in New York; I was the support teacher in an inclusive classroom in which about half the kids had a learning disability or struggled with behaviour challenges. The students in my class didn’t have significant intellectual disabilities, but they were negotiating a lot of things, including poverty. That was when I started to better understand inclusion, because I saw the community that formed in this classroom. It became their lifeline to each other. Not just for the kids with disabilities, but the kids without: they were mentors and they were friends. In the Bronx, the kids looked out for each other. I had never felt a sense of community like I did when I worked in that school.

In my next job, I was working in Richmond, just south of Vancouver. I was a support teacher in a high school, grades eight to 12. Here, I was working with kids with intellectual disabilities including Down syndrome and autism. I had 18 on my caseload and we were totally self contained in the corner of the school. No one even knew we were there, and it felt like we were in prison. I would go to staff meetings and people didn’t even know who I was, let alone who my kids were. We had our own entrance to the school; we had special buses and to me, it didn’t feel right. It seemed to me that I could meet their needs in this program, but in this building, we might as well not have been there.

Eventually, we started to get the kids more included in elective classes; we still weren’t even touching academics. The kids in the school had all grown up together in an inclusive elementary environment, and so when the kids with disabilities started to be included again, it was like an incredible reunion. All of a sudden, these kids were coming back together in grade eight and nine. I can’t even describe for you the excitement they had. It made me realize how much they need each other.

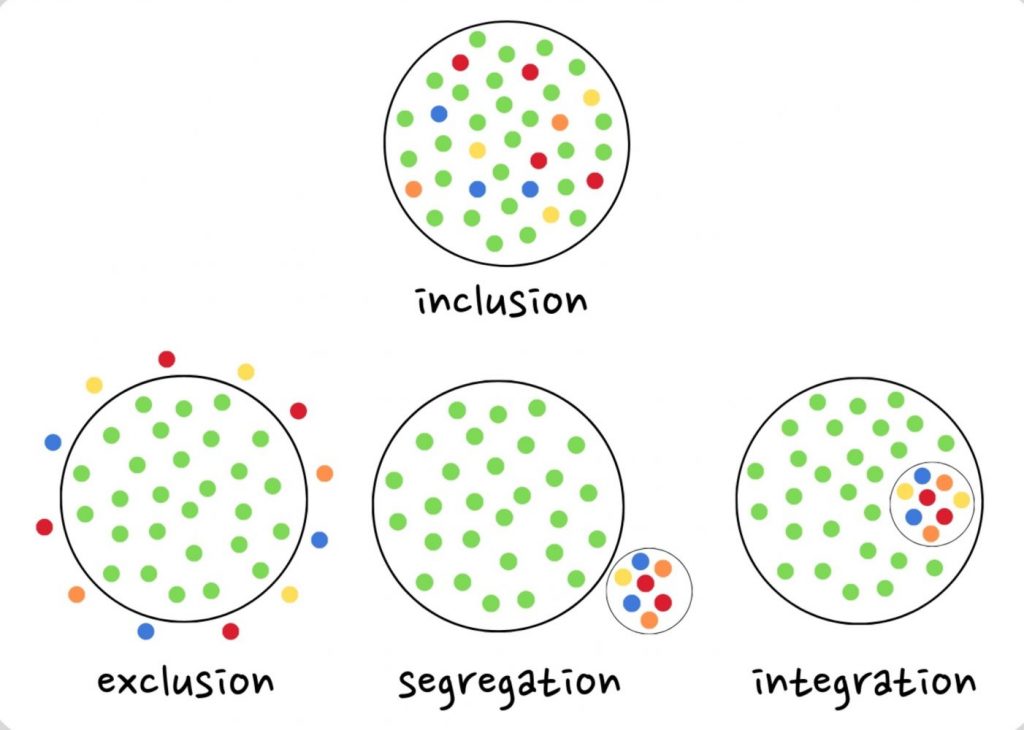

3.21: Let’s get into the buzzwords. How would you define and distinguish between exclusion, segregation, integration, and inclusion?

SM: Those words describe the history of inclusion, how we got to where we are today. It’s a continuum that doesn’t necessarily just apply to disability; you could apply this historical timeline to many marginalized populations.

With regards to disability, where we started historically was with total exclusion – not only from school, but from family and community. We often associate that with the institutionalization movement. Over time, however, self- and their families fought back against institutionalization. Eventually it got to where individuals with disabilities were in their communities, but they were going to separate schools because it was assumed that they needed something different. That’s segregation, which people at the time thought was better than exclusion, but wasn’t, really.

At that point you had kids in different schools and parents said, “Hey, I have kids with and without disabilities; why am I taking them to different schools?” So, another shift began from segregating kids with disabilities to having them come to their neighbourhood school together with their siblings and peers. The difficulty with this shift, however, is that students with disabilities often ended up coming to the same building, but a separate part of that building, or in a classroom, but doing separate work and activities from their peers. This is where a lot of schools are right now, which is integration.

The next step in advocacy came from teachers who said, “Well, just physically existing and sharing space in a classroom, that’s actually not enough.” It’s often going to result in behaviour problems because the kids aren’t connected and engaged. What we really need is inclusion.

If kids don’t feel like they belong, they’re going to communicate in whatever way makes sense for them that it’s not working. And if a kid who needs support to communicate that something isn’t working, it often gets misinterpreted as challenging behaviour. The problem is, people look at that behaviour and say, “Oh, inclusion’s not working for that kid. We have to go back to segregation.” In reality, it is not that inclusion is not working; it’s that we’re not there yet. So, a lot of the shifts that are happening in schools right now are about how we move from a container where kids are physically together, to facilitating authentic community. How do we create a space where people feel like they belong, where they choose to be there, where we have a voluntary place for kids to engage with each other? This is inclusion.

The latest evolution is the realization that it’s not just people with disabilities who need that feeling of belonging despite difference, because every person is different. Teaching to diversity is another shift in understanding inclusion, by changing our questions from: How do we include people who are different, to how do we teach to difference? It starts by acknowledging all the ways that kids are diverse, which includes not just disability, but culture, gender, race, language, all the things that make us who we are.

3.21: Picture a child with Down syndrome in a fully inclusive scenario. How does the school ensure the unique learning and social needs of that child are being met?

SM: My thoughts on this have changed. As I went to school and became a special educator, I was taught to make my plan for kids without disabilities, and then modify that plan for individuals with disabilities. Now the problem with that is that it’s a retrofit approach. And if you retrofit anything, whether it’s a building or a plan or supper, it’s going to take more resources; that is, more time, more funding and more people to do that work. So what I’ve really learned, especially in doing this in high school, is that if we’re going to include kids who have intellectual disabilities, or anyone else for that matter, we can’t look at any of their needs as an aftereffect.

If your approach is to make a regular plan and then retrofit it, you’re going to be retrofitting it for 28 out of 30 kids. That’s why people think there’s a really high workload with inclusion, but it’s not the diversity that’s the problem; it’s the plan that’s the problem. So when I think of how I’m going to meet the needs of the child in my classroom with Down syndrome, I am going to think to myself, okay, how am I going to make a plan that includes the needs of my student with Down syndrome from the start, so that I don’t have to adapt and modify it for them afterwards?

Assume from the start that you’re working with diverse people, and the child with Down syndrome is going to be one of those people. So rather than thinking, “I have to do this extra work for one kid,” I’m thinking, first, who are my kids? What are their strengths? What are their interests? What are their needs? I need to do that first, and then I make a plan that addresses that range. And so when I think of successful inclusion, it’s about how are we supporting teachers to design from a range from the beginning, as opposed to supporting teachers to adapt and modify for all of the individual kids who aren’t successful from the start?

It’s based on strengths. Regardless if they have a disability or not, everyone’s going to have strengths. Everyone can do something. So, when I’m thinking about planning and using the curriculum, I’m thinking about that: What can everybody do? And then, how do I add on complexity? That is so much easier than starting from the most complex version of the lesson, and then trying to go backwards and simplify after the fact.

The metaphor that I use is the baked potato. This is what inclusion means to me: If I’m in a classroom, I ask myself, “What can everybody do?” Whether it’s math or English or social studies or physics, it doesn’t matter. What can everybody do? That’s my potato. I want everyone to be able to eat a potato at the end of this day, at the end of this class or the end of this year. Okay. Now, some people will be okay with the potato, right? Other people will need more toppings. So I’m going to teach everybody all the topping options. I’m going to show them what butter is. I’m going to show them what green onions are. I’m not going to make little green onion groups. I’m going to teach what green onions are to everybody. And what we’re really realizing is, even when I think people are only going to eat the potato, if it’s taught in a way that everyone has access to complexity, kids will put on more toppings than we think. The kid who you would never imagine would eat green onions, will be piling them all on top. That is the beauty of design. We end of meeting the needs of kids who we would never have imagined needed a support.

3.21: Are there benefits to having children with developmental disabilities learning and interacting with one another? If so, how would you facilitate that without sacrificing inclusion?

SM: The group that you’re describing is called a community of identity, where people of like identity come together. These spaces are very safe. These spaces have very high senses of belonging. So, for example, I’m gay. I have gay friends and we hang out sometimes. The problem is not the community. The problem is the criteria for the community.

As a queer person, if someone who wasn’t queer said, “All you queer people go hang out,” and that’s the only place that I was allowed to go and the only relationships I was allowed to have, that is totally different than me hanging out with queer people that I choose. And it’s not the only community that I feel support and belonging in.

Absolutely, kids need a sense of identity and a collective sense of community with other people with disabilities. I am a huge advocate for that. How I suggest we do it, though, is not at the expense of inclusion and diversity. It’s at the expense of segregation, which is when someone else decides when and how it happens.

How we did that in our school was to introduce a class that was listed as an elective. It was designed for kids with disabilities, and it provided explicit support around life skills, community skills, literacy, etc. It wasn’t a mandated course that they had to take. Did most of them take it? Yes. But it wasn’t because they had a disability. A lot of them were in there because that’s where their best friends were. It’s about creating these spaces where people can be empowered to envision what that space looks like for themselves, rather than assuming this is the only space where students will be successful and dictating it without any other options.

3.21: Where do inclusive plans sometimes go off the rails?

SM: I said something on Twitter the other day that got me in a bit of trouble. I said, “There’s no amount of funding that can make someone believe that inclusion is worthwhile.” What I meant to say by that was, there’s no amount of funding that can make someone not an ableist. Because I realized that ableism is a discrimination; it’s an attitude. Inclusion is a practice. Inclusion is what you do. And so, a huge barrier to inclusion is ableist attitudes and people not presuming competence, which means people come up with reasons why inclusion can’t happen because they think kids aren’t capable.

We’re going through this whole thing with racism right now, right? We don’t even realize that the structures in place are historically racist. And we can learn from this movement by identifying historically ableist structures that have also existed for a long time. These structures are so engrained that we can’t even see that it’s a problem. Kids are existing in a system that’s designed to discriminate. How it’s often expressed is, “There’s not enough money. There’s not enough supports.” And I’m like, “Yeah, except that the funding that we advocate for is being used in a system that’s supporting discrimination.”

So that’s the number one barrier to inclusion, the ableist infrastructure of education. Number two, I would say the non-optimal use of resources. And I would say number three is leadership. If leadership doesn’t believe, no one’s going to believe. Whether that’s school or district leadership, they make the decisions about how resources are used. If you have a leader who believes, you will have inclusion. And that’s why we see schools that are really inclusive and across the street another school that isn’t, or districts that are really inclusive and another one that isn’t: it comes down to leadership. And it’s very hard because many leaders don’t have experience with disability.

3.21: Bridging the gap between theory and practice, how does someone get started in increasing the places where individuals feel included?

SM: Ultimately, a lot of it comes down to the teacher’s plan. And just as you can’t force kids to belong, you can’t force teachers into this either. All we can do is create conditions for people to engage. So, we have to actually enact the same inclusive principles with educators that we do with our kids. We create conditions for teachers to engage in the work, which means they’re released, which means they have time to collaborate, which means that they have not necessarily just another EA in the classroom or another iPad, but a complete infrastructure for collaboration.

It’s very much a process. We have to work with schools and teachers over time. It can’t just be a one or two-hour workshop. It’s an inquiry model. Where are you now? What’s your next step? What are you going to try next? We’re modeling the practice of learning with teachers in the same way we would with students. What are you doing already? What can you do? What do you want to try next? When are you going to try it? What supports do you need to try that? And the biggest impact that I’ve seen in shifts from theory to practice is in school districts that have that infrastructure of collaborative professional development.

3.21: What impacts has COVID-19 had on inclusivity, and are you worried about the long-term ramifications?

SM: COVID has been interesting because I’ve seen some really positive things and I’ve seen some really not-so-positive things. I’m always an advocate for looking to your kids who need the most support first. What happened with COVID was, because there was such a fast and massive shift to home learning, disabilities were left till last. We forgot that if you can figure it out for kids with disabilities, everyone else will be fine.

Teachers quickly learned, if you’re just going to sit in front of a screen for six hours and talk at kids, it’s not going to work. They had to develop some really critical inclusive practices, like choice, and like targeted mini lessons and options for showing what you know. All these important practices that you must do if your kids are going to be engaged, teachers were forced to do it by necessity. As a result, I saw some incredible practices, because teachers were just like, “If I don’t do this, my kids aren’t going to sign on.” Some of the planning that I saw and how it addressed diversity was brilliant. And so I’m hoping that when all this starts to get back to normal a little bit, those practices will be maintained, because even if kids are all in one room there still needs to be choice, and there still needs to be more than one way to show what you know, and there still needs to be targeted mini-lessons, not 90-minutes of lecturing. All those practices are going to help kids with intellectual disabilities when they come back to their classrooms.

We’ve also been reminded that school is not the only place where we learn. So how do we capitalize on learning in every place? Let’s make all places purposeful. Let’s make baking purposeful; let’s make video games purposeful. Let’s make walking down the road purposeful, because there is such a misunderstanding that school’s the only place where learning counts. If we truly believe that learning happens everywhere and we’re honouring the learning that happens in homes, that’s also aligned to reconciliation efforts, which is also a really important part of this inclusive conversation. Learning does not just count in this building that kids are forced to go to. We can honour the knowledge and learning that every family has.

3.21: Finally, the big picture. Do you see classroom inclusion improving in Canada?

SM: Yes. Well, here’s the thing. Now that I’ve had the opportunity to travel around the world, I think Canada is situated further along the inclusion journey than many places. And within Canada, there are certain provinces that are further along than others. And within provinces, certain districts are further along. And within districts, certain schools are further along in the journey than others.

I think there are examples of true inclusion everywhere I’ve gone. The problem I see with inclusion being a destination is that I don’t think it is. I think it’s, “How do we get better at this all the time?” Because even when you get there, it’s going to evolve again into something else. When I work with schools, I’m trying to determine where they are today, and then help them commit to the next step. Now that we know better, let’s do better.

What often happens is we think, “We can’t be inclusive because…,” and then you have this long list of reasons that often are tied to resources. Instead, we must commit to getting better all the time, regardless of resources. You can have two schools in the same district, in the same city, across the street from each other, with the same resources, and one is exceptionally inclusive and one isn’t. It really comes down to where are you now, and how do you get better? Because we can all do better.

Bottom line: Do I believe that it’s getting better? Yes. Do we have a long way to go? Yes.

Shelley Moore is a highly sought-after teacher, researcher, consultant and storyteller and she has worked with school districts and community organizations throughout both Canada and the United States. Her research and work have been featured at national and international conferences and is constructed based on theory and effective practices of inclusion, special education, curriculum and teacher professional development. Find out more about Shelley on her website fivemooreminutes.com or follow her on Twitter @tweetsomemoore.